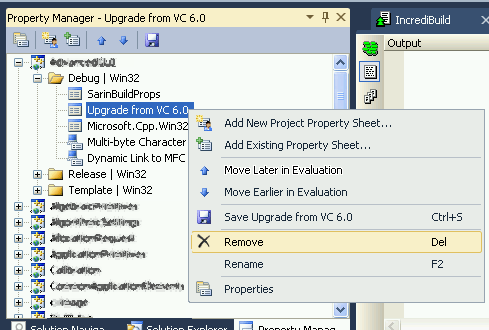

Here’s the symptom – you stop and inspect a stack:

Note the message at the second line:

Frames below may be incorrect and/or missing. No symbols loaded for XXXXX.dll.

Chances are you read it once years ago and ignored it ever since. If so, that’s a shame – because the debugger is dead serious about it.

You load some missing symbols (either from the modules window, or by right clicking a line on the stack window), and the stack changes. Often, the code displayed (topmost frame where code is available) is seen to be misleading – it’s nowhere to be found on the updated stack!

This happens a lot, e.g. when uncaught exceptions are thrown outside your own code, when you pause execution, or when switching to a different thread while stopped at a breakpoint. Essentially – it happens whenever stack walking has to start from an optimized module without loaded symbols (in particular, MS modules like ntdll above).

First Corollary

| Loading MS-symbols is NOT optional! |

Hopefully every dev in the civilized world knows what these are and how to get them (MS made it considerably easier since VS2008), so I will not rehash. What is not widely obvious, is that without them there’s a good chance you’re looking at wrong stacks.

Second Corollary

Apparently stack walking is harder than it seems, and depends in some way on debug information.

That was news to me, and called for some research.

Naive Stack Walking

[A full x86-stack-layout tutorial is an undertaking way beyond the extent of my spare time. Try e.g. here for a nice read. The following is a very rough and minimal description]

Ignoring most stack content (function parameters, local variables, calling conventions, exception handling, buffer security and such), a naive layout of an x86 stack frame is something like –

Memory address: Stack elements:

^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

0x104FD8 | | Parameters | \

| +----------------------------+ |

0x104FD4 | | Return address, routine 2 | |

| +----------------------------+ > Stack frame 3

0x104FD0 +--| EBP value for routine 2 | |

+----------------------------+ |

0x104FCC +->| Local data | / <-- Routine 3's EBP

| +----------------------------+

0x104FC8 | | Return address, routine 3 | \

| +----------------------------+ |

0x104FC4 +--| EBP value for routine 3 | |

+----------------------------+ > Stack frame 4

0x104FC0 | Local data | | <-- Current EBP

+----------------------------+ |

0x104FBC | Local data | /

+----------------------------+

0x104FB8 | | <-- Current ESP

\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/

Where the Extended Base Pointer slots store the contents of the register that marks the start of a stack frame. So obtaining a stack trace should be as simple as –

- Walking the chain of EBPs (each EBP slot on a stack frame points to just below the EBP slot of its parent frame) to form the stack of frames.

- From above each EBP slot, take the stored EIP and use it to decipher the calling module and the calling function name.

Phase (2) is indeed best done with symbols, but can be achieved with some success (exported functions only) with only linker map files. Either way, this description cannot account for the dependency of the stack-frames partition itself upon the presence of symbols! There has to be more to the story.

First Exception – FPO

Ever since the Intel 386, both ESP and EBP can serve as reference points for local stack variables, and faced with the scarcity of registers on x86 systems it was a tempting optimization to drop EBP dedicated usage altogether. This is called Frame Pointer Omission, and indeed mandates dedicated stack-walking assistance info in the PDB – as the traditional EBP chain breaks completely once a single stack frame uses FPO. However, FPO have been rarely used in practice and completely disabled in MS builds since Vista so it cannot possibly account for all occurrences of bad stack traces.

Others Exceptions?

Well, probably – but not documented ones. I have several reasons to believe so:

(1) StackFrameTypeEnum (used by IDiaStackFrame) indeed includes FrameTypeStandard and FrameTypeFPO, but also other frame types (notably FrameTypeFrameData).

(2) The VC team blog did hint that a PDB includes, quote,

the unwind program to execute to walk to the next frame

(3) I’ve witnessed these symptoms on dumps taken from Win7 machines – and AFAIK Win7 binaries were compiled without FPO.

(4) The venerable John Robbins answered an email of mine, saying:

Yes, unless you have all symbols loaded for a native application, you can never truly trust the stacks. You’re right that MSFT no longer uses FPO, but if the symbols for a DLL in the stack are not loaded, the StackWalk64 API, which all debuggers use, goes through heuristics to walk the stack. Heuristics is a fancy name for guessing. J For example, if you don’t have the PDB files loaded for a module, the stack walking code will show you the closest symbol to an address. That symbol could actually come from another DLL. Once you load the PDB file, the correct symbol is available so the address symbol will change in the call stack window.

Can’t say I really got to the root of this dependence on PDBs, though. If anyone out there cares to shed more light over this, I’d love to hear!