(Note: most of this post avoids developer jargon, in hope of being useful to all users)

Did you ever give a media-rich presentation, and had to sheepishly apologize to the audience when some movies just wouldn’t play? Did you ever mail a presentation that the recipient was unable to play?

I once made a spectacular product PowerPoint presentation that no costumer ever saw, since none of the sales persons were able to play it. I still attend an embarrassing amount of presentations that fail to present their media properly. The common maven answer is ‘it must be a missing codec’ but, as usual, the full story runs much deeper.

The following investigation applies to PowerPoint 2003 over Windows XP – but from reading around I get the impression that the same issues and solutions apply to PowerPoint 2007, either over Vista or XP.

First – make sure your movie plays under Windows Media Player! If it doesn’t – its probably indeed a codec issue. Download a codec pack and be done with it. There are also tools that can pinpoint a missing or corrupt codec – but this post is about PowerPoint, so let’s assume the movie plays fine outside it.

Second – try to run the movie in Media Player (confusingly enough and despite the windows title, this is not Windows media player): in the start\run prompt type mplayer2, then browse to your movie. If you have Vista skip this test, as you don’t have that player.

Unlike some say, strictly speaking PowerPoint does not use media player – but rather both use the same mechanism, MCI (more below). So – no luck with Media Player? Good. Read on.

Cookbook solution

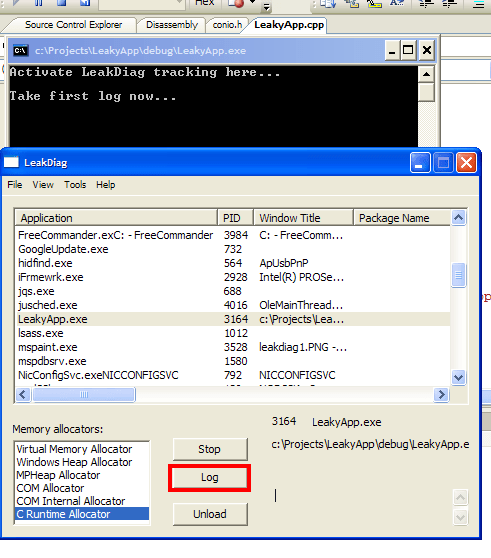

Here’s a visual rehash of the instructions for PowerPoint 2003 (the link contains instructions for PowerPoint 2007 too) on how to embed a Windows Media Player control, that would play your movie.

1. Under ‘View/Toolbars’, check ‘Control toolbox’.

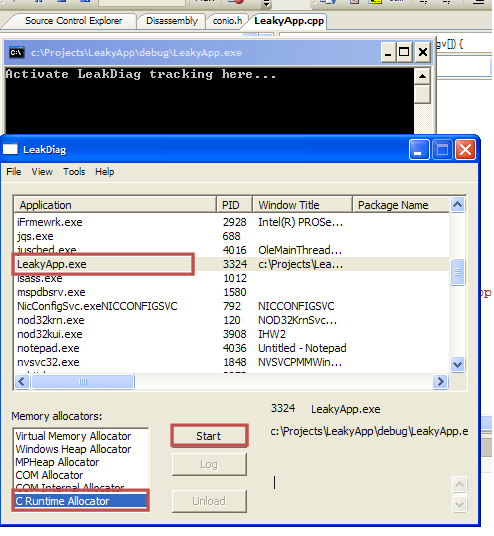

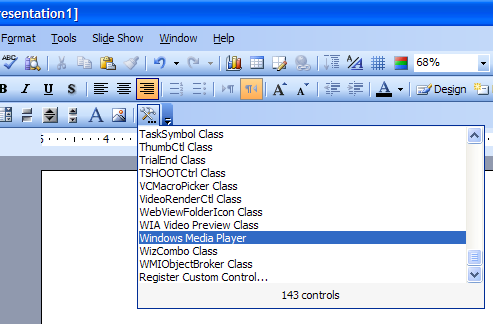

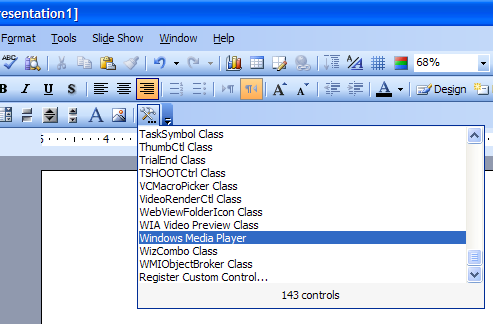

2. In the new toolbar click ‘More Controls’, scroll down to pick ‘Window Media Player’, then click-n-drag to mark the movie rectangle on the slide.

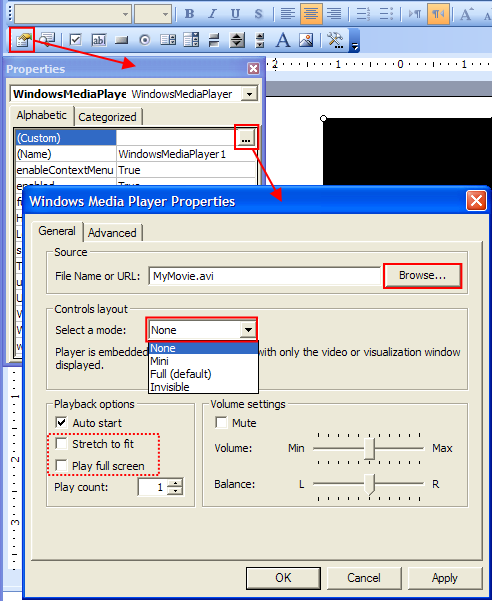

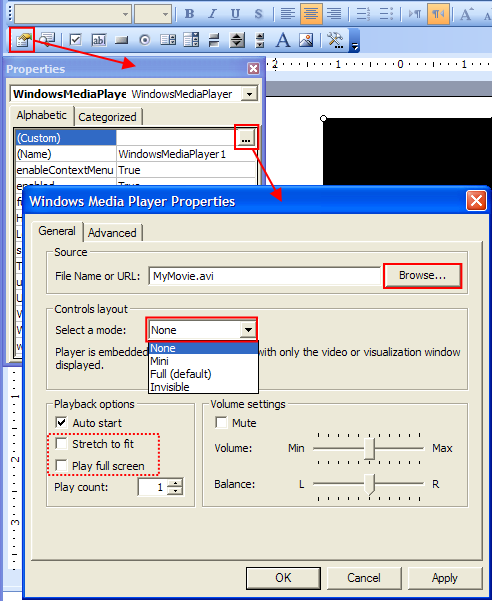

3. make sure the new object is selected, then click ‘Properties’ (available via right click too).

4. Click the ellipsis to the right of ‘Custom’. Browse to the movie of your choice. To reproduce the appearance of a simple movie, in the ‘Select a mode’ combo – select ‘None’. (you might, however, find the newfound alternatives useful – check them out).

Run the slide – your movie should at least play now.

If you checked ‘Stretch to fit’ or ‘Play full screen’, you may discover that either they had no effect, or were unsaved and have no effect in the next run. This is in fact a known WMP control bug – that remains unsolved since (at least ..) that 2004 post from Microsoft. A workaround is in order.

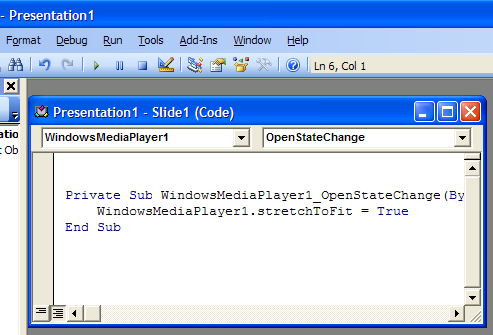

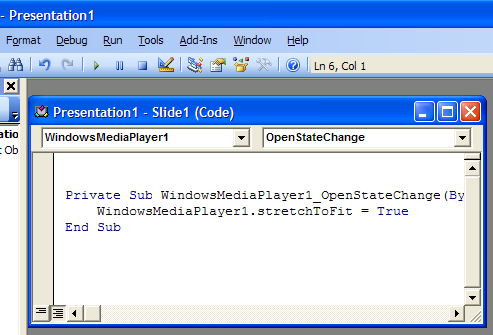

5. Double click the WMP object, and a VBA window would open. Don’t be alarmed if its unfamiliar – all you have to do is paste the following code:

Private Sub WindowsMediaPlayer1_OpenStateChange(ByVal NewState As Long)

WindowsMediaPlayer1.stretchToFit = True

End Sub

When trying a similar trick with ‘fullScreen’ property instead of ‘stretchToFit’, I get a run-time error – probably another WMP ActiveX bug. Oh well, you can easily stretch the movie area to a full slide in the first place.

Under the hood

(Note: switching back to developer lingo)

The support article did say that ‘Some media clips that were created after PowerPoint was released may not play properly’. But even support can say more: ‘PowerPoint does not allow you to insert certain types of movie files directly if there are no available Media Control Interface (MCI) extensions for that type of movie.’ (which, strictly speaking, is wrong – I wish PowerPoint would complain when inserting the movie and not just play a blank).

Huh? Media control what?

Apparently, it’s an MS API – a predecessor to DirectShow that’s not technically deprecated (heck, PowerPoint uses it), but even wikipedia describes it as ‘aging’. It uses two registry keys: ‘HKLM\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows NT\CurrentVersion\MCI Extensions’ maps file extensions to abstract MCI-devices, and HKLM\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows NT\CurrentVersion\MCI32 maps the devices to concrete driver dll’s. So a ‘missing MCI extension’ means that in the MCI Extensions key, the ‘avi’ value (e.g.) is either missing or does not hold the string ‘avivideo’ as it should.

Austin Myers, PowerPoint MVP and maker of the PlaysForCertain add-in, gives an excellent summary of related newsgroup discussions. turns out quite a few rogue media players – notably some versions of QuickTime, Xing, Real Player and WinAmp – used to modify these registry keys. If any of these messed up during install or uninstall, your machine remained with dysfunctional MCI registry keys!

Which brings us to an –

Alternative fix

You can try and fix MCI issues by modifying these keys (usual registry disclaimers applies: back it up, know what you are doing, yada yada). For reference, here are two excerpts from my own registry:

[HKLM\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows NT\CurrentVersion\MCI Extensions]

"avi"="avivideo"

"mpg"="MPEGVideo"

[HKLM\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows NT\CurrentVersion\MCI32]

"AVIVideo"="mciavi32.dll"

"MPEGVideo"="mciqtz32.dll"

Check out both Myers’ article and this 2003 WINE patch for full configurations on other machines – just act judiciously, as these configurations may greatly vary.

So, which solution is better?

The real game here is to get a ppt to play its movies not only on your machine, but on any machine – whether if you send it by mail, place it somewhere public or carry it around on a USB stick. In fact, the previously mentioned PlaysForCertain commercial add-in tries to achieve just that by converting linked movies into a format and codec that are as common as they can possibly be.

While I have practically never seen a windows machine without WMP (never mind why), I came across a good few machines with messed up MCI settings. So, excluding commercial solutions, I whole heartily believe your best bet would be to stick with the WMP-control solution.

Do tell me if it worked for you, and (more importantly) if not!